[h=2]Half of people living in Illinois and Connecticut want to get the hell out[/h]

<figure>

<figcaption class="p-caption"> Not every Chicagoan is as happy as this kid. Half of Illinoisans say they'd get out if they could. Getty Images </figcaption> </figure>

<figcaption class="p-caption"> Not every Chicagoan is as happy as this kid. Half of Illinoisans say they'd get out if they could. Getty Images </figcaption> </figure>

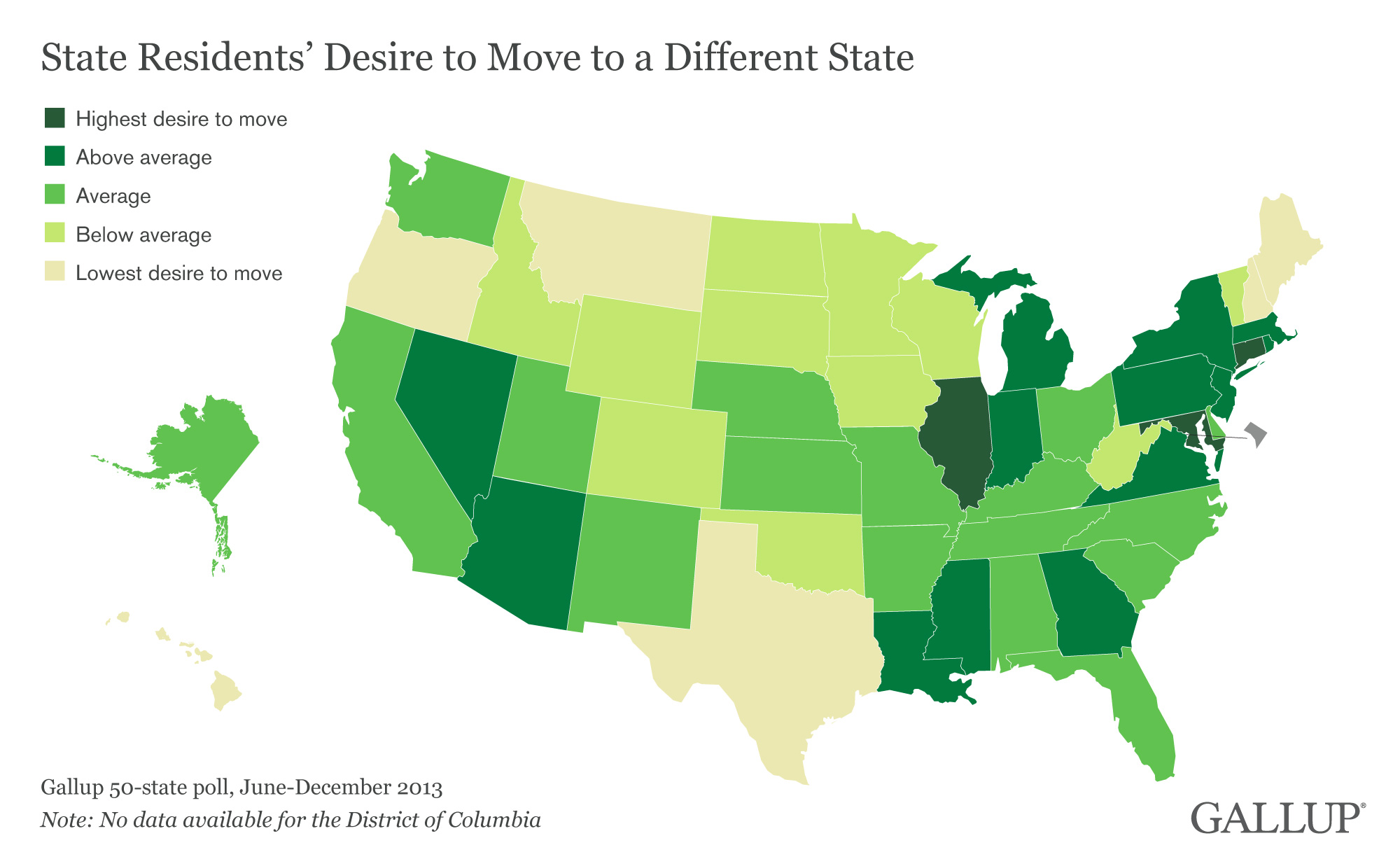

New data is out on the states people want to leave, and it's tailor-made to troll all your Facebook friends from Illinois and the northeastern Amtrak corridor.

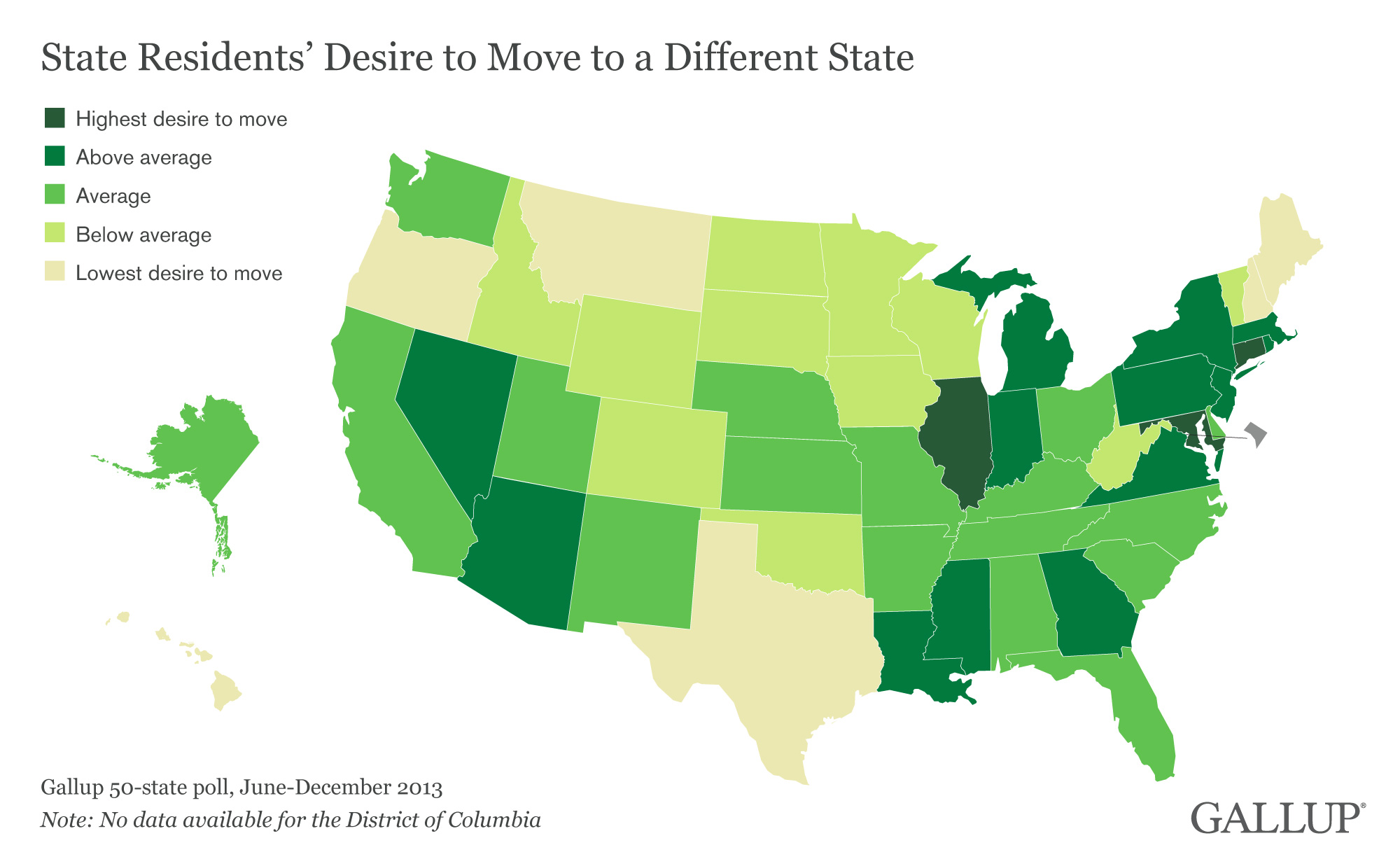

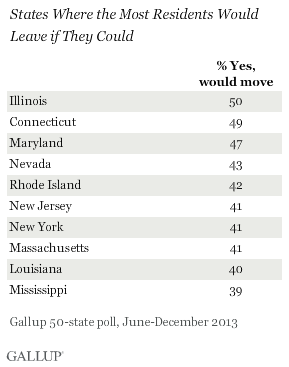

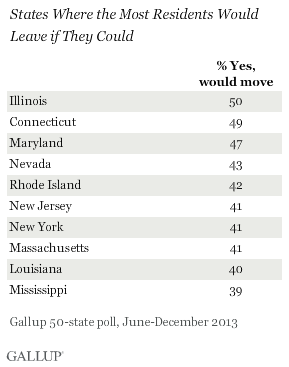

Gallup asked people around the country whether they would move away from their states, given the chance. As it turns out, half of Illinois residents and 49 percent of all Connecticutians (Connecticutese? Connecticuters?) want to change states. In addition, it looks like a good chunk of the northeastern seaboard is just itching to pack up a U-Haul.

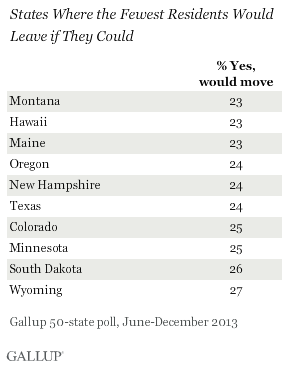

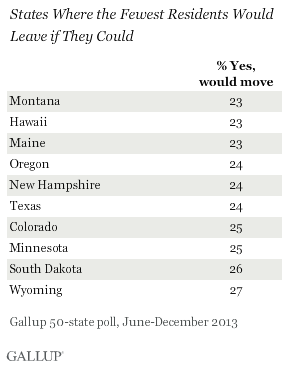

Montanans, Hawaiians, and Mainers are least likely to say they'd want to leave, with fewer than one-quarter of those residents saying they'd move. Altogether, only 33 percent of all Americans surveyed said they'd leave their current states.

Meanwhile, in nine states, 40 percent or more of the people want to get out, including around half of all Illinoisans, Marylanders, and Connecticuterians.

It's fascinating data, and if you're from the relatively content upper plains, you can feel comfortably superior. If you're from one of those dark green states, you can shake your fist at the sky in anguish.

Or you can just, you know, get out.

All these people say they would leave if they could, but far fewer actually will, which might in a certain sense be good — imagine the epic moving-box and bubble-wrap shortage if one-third of all Americans moved to a new state.

But only six percent of all people said they were either very or extremely likely to change states in the next year, and even that is higher than the number of people who will likely move. That share of people who as of July 2013 were in a different state from a year ago was around 1.5 percent.

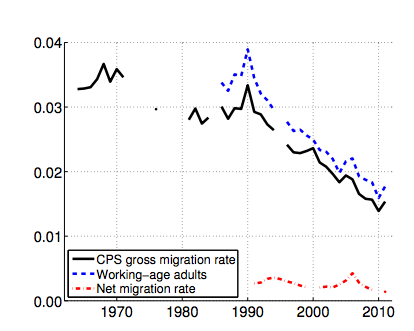

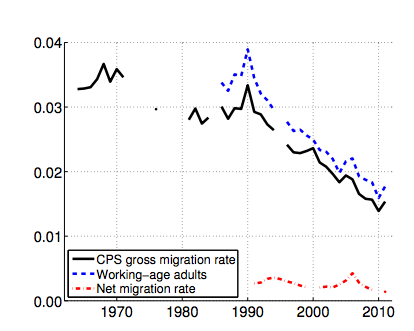

That's a much lower share than it used to be. Interstate migration has fallen in a big way over the last twenty years. A 2013 paper from the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis showed this.

Thanks to those unsightly gaps, the chart isn't perfect, but it clearly shows that the gross interstate migration rate — the black line showing the share of the US population that shifted from state to state in any given year — fell by roughly half, from almost 3 percent to around 1.5 percent, between 1990 and 2011.

Americans have stopped changing states, and that may be a very bad thing. During and just after the recession, the ever-dropping moving rate made everyone wring their hands: a collapsed housing market and a profound lack of jobs both contributed to and resulted from a lack of migration.

When there are no jobs anywhere, after all, people have less of a reason to move. And when the housing market is stagnant, people can't go get the jobs that do happen to pop up. In other words, the would-be factory worker who can't sell her house in Memphis to move to Cincinnati, where there are jobs, can't get that job and spend that paycheck and create more jobs. Or maybe that person just wants to wait for housing prices to pick back up again before selling.

Because of this, it could be both a promising sign and an economic booster if Americans start to move more; notably, a lot of the states people say they'd least like to leave also have low jobless rates, and people who would most like to leave are often in states where the jobless rate is high.

Plus, among Americans who say they plan to leave their states, the most common reason given was work- or business-related — a reason given by 31 percent of respondents. Different states, however, had different mixes of reasons; New York, Illinois, and Maryland residents all cited taxes as a key reason. New York and Connecticut residents were also significantly more likely to cite a high cost of living.

All that said, there's another story about why people are staying put, and it's not about recessions. After all, the decline in mobility started way before the recession. Rather, it may be all about a more homogeneous US economy, not to mention the internet and cheap travel.

The economists who made that above chart, Greg Kaplan and Sam Schulhofer-Wohl, argued that the decline in moving in part happened because US jobs got less geographically specific, as they put it. Translated, that means it's easier than it used to be to find a lot of the same sorts of jobs across a lot of different cities, as the Economist noted in 2012. A shift away from the goods-producing sector to services has helped this happen. Common services jobs, like healthcare and waitressing, can be done anywhere. But a lot of goods-producing jobs (manufacturing, mining, logging) have to be done in particular places (i.e. wherever the factories, mines, or trees are).

Likewise, there's now more fluid information. People can easily look up places they might want to live. This could also be a factor that keeps people in place — they can research and hem and haw over a move, rather than crossing their fingers and driving across the country.

All of which may mean that even if Illinoisans and Connectici and really anyone else is just sick of their state, they're less likely to do anything about it than they were 20 years ago. The question of whether that's a good or bad thing remains a mystery.

<figure>

New data is out on the states people want to leave, and it's tailor-made to troll all your Facebook friends from Illinois and the northeastern Amtrak corridor.

Gallup asked people around the country whether they would move away from their states, given the chance. As it turns out, half of Illinois residents and 49 percent of all Connecticutians (Connecticutese? Connecticuters?) want to change states. In addition, it looks like a good chunk of the northeastern seaboard is just itching to pack up a U-Haul.

Montanans, Hawaiians, and Mainers are least likely to say they'd want to leave, with fewer than one-quarter of those residents saying they'd move. Altogether, only 33 percent of all Americans surveyed said they'd leave their current states.

Meanwhile, in nine states, 40 percent or more of the people want to get out, including around half of all Illinoisans, Marylanders, and Connecticuterians.

It's fascinating data, and if you're from the relatively content upper plains, you can feel comfortably superior. If you're from one of those dark green states, you can shake your fist at the sky in anguish.

Or you can just, you know, get out.

All these people say they would leave if they could, but far fewer actually will, which might in a certain sense be good — imagine the epic moving-box and bubble-wrap shortage if one-third of all Americans moved to a new state.

But only six percent of all people said they were either very or extremely likely to change states in the next year, and even that is higher than the number of people who will likely move. That share of people who as of July 2013 were in a different state from a year ago was around 1.5 percent.

That's a much lower share than it used to be. Interstate migration has fallen in a big way over the last twenty years. A 2013 paper from the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis showed this.

Thanks to those unsightly gaps, the chart isn't perfect, but it clearly shows that the gross interstate migration rate — the black line showing the share of the US population that shifted from state to state in any given year — fell by roughly half, from almost 3 percent to around 1.5 percent, between 1990 and 2011.

Americans have stopped changing states, and that may be a very bad thing. During and just after the recession, the ever-dropping moving rate made everyone wring their hands: a collapsed housing market and a profound lack of jobs both contributed to and resulted from a lack of migration.

When there are no jobs anywhere, after all, people have less of a reason to move. And when the housing market is stagnant, people can't go get the jobs that do happen to pop up. In other words, the would-be factory worker who can't sell her house in Memphis to move to Cincinnati, where there are jobs, can't get that job and spend that paycheck and create more jobs. Or maybe that person just wants to wait for housing prices to pick back up again before selling.

Because of this, it could be both a promising sign and an economic booster if Americans start to move more; notably, a lot of the states people say they'd least like to leave also have low jobless rates, and people who would most like to leave are often in states where the jobless rate is high.

Plus, among Americans who say they plan to leave their states, the most common reason given was work- or business-related — a reason given by 31 percent of respondents. Different states, however, had different mixes of reasons; New York, Illinois, and Maryland residents all cited taxes as a key reason. New York and Connecticut residents were also significantly more likely to cite a high cost of living.

All that said, there's another story about why people are staying put, and it's not about recessions. After all, the decline in mobility started way before the recession. Rather, it may be all about a more homogeneous US economy, not to mention the internet and cheap travel.

The economists who made that above chart, Greg Kaplan and Sam Schulhofer-Wohl, argued that the decline in moving in part happened because US jobs got less geographically specific, as they put it. Translated, that means it's easier than it used to be to find a lot of the same sorts of jobs across a lot of different cities, as the Economist noted in 2012. A shift away from the goods-producing sector to services has helped this happen. Common services jobs, like healthcare and waitressing, can be done anywhere. But a lot of goods-producing jobs (manufacturing, mining, logging) have to be done in particular places (i.e. wherever the factories, mines, or trees are).

Likewise, there's now more fluid information. People can easily look up places they might want to live. This could also be a factor that keeps people in place — they can research and hem and haw over a move, rather than crossing their fingers and driving across the country.

All of which may mean that even if Illinoisans and Connectici and really anyone else is just sick of their state, they're less likely to do anything about it than they were 20 years ago. The question of whether that's a good or bad thing remains a mystery.