http://sports.yahoo.com/news/the-education-of-yoan-moncada-201005541.html[h=1]The education of Yoan Moncada[/h]

<cite class="byline vcard top-line">By Jeff Passan<abbr>3 hours ago</abbr></cite>

Content preferences[h=3][/h]

<button class="done-btn" data-rapid_p="7">Done</button>

<!-- google_ad_section_start --><meta content="2016-09-02T20:10:05Z" itemprop="datePublished"><meta content="The education of Yoan Moncada" itemprop="headline"><meta content="" itemprop="alternativeHeadline"><meta content="https://media.zenfs.com/creatr-images/GLB/2016-09-02/f861dae0-714a-11e6-a338-0dc38813bc8b_GettyImages-544083458.jpg" itemprop="image"><meta content="It is everything the teenage boy did not know, did not understand, when he left Cuba and arrived in the United States with an ability to play baseball that inspired a bidding war like none seen before. Yoan Moncada is finally here, officially with the Boston Red Sox, ready to fulfill a promise he made last year. It was February, and he sat in a restaurant at Southwest Florida International Airport, polishing off a filet mignon and a hamburger, each well-done enough to resemble a hockey puck." itemprop="description"><figure><figure class="cover get-lbdata-from-dom go-to-slideshow-lightbox" data-orig-index="0"> View gallery

.

</figure>

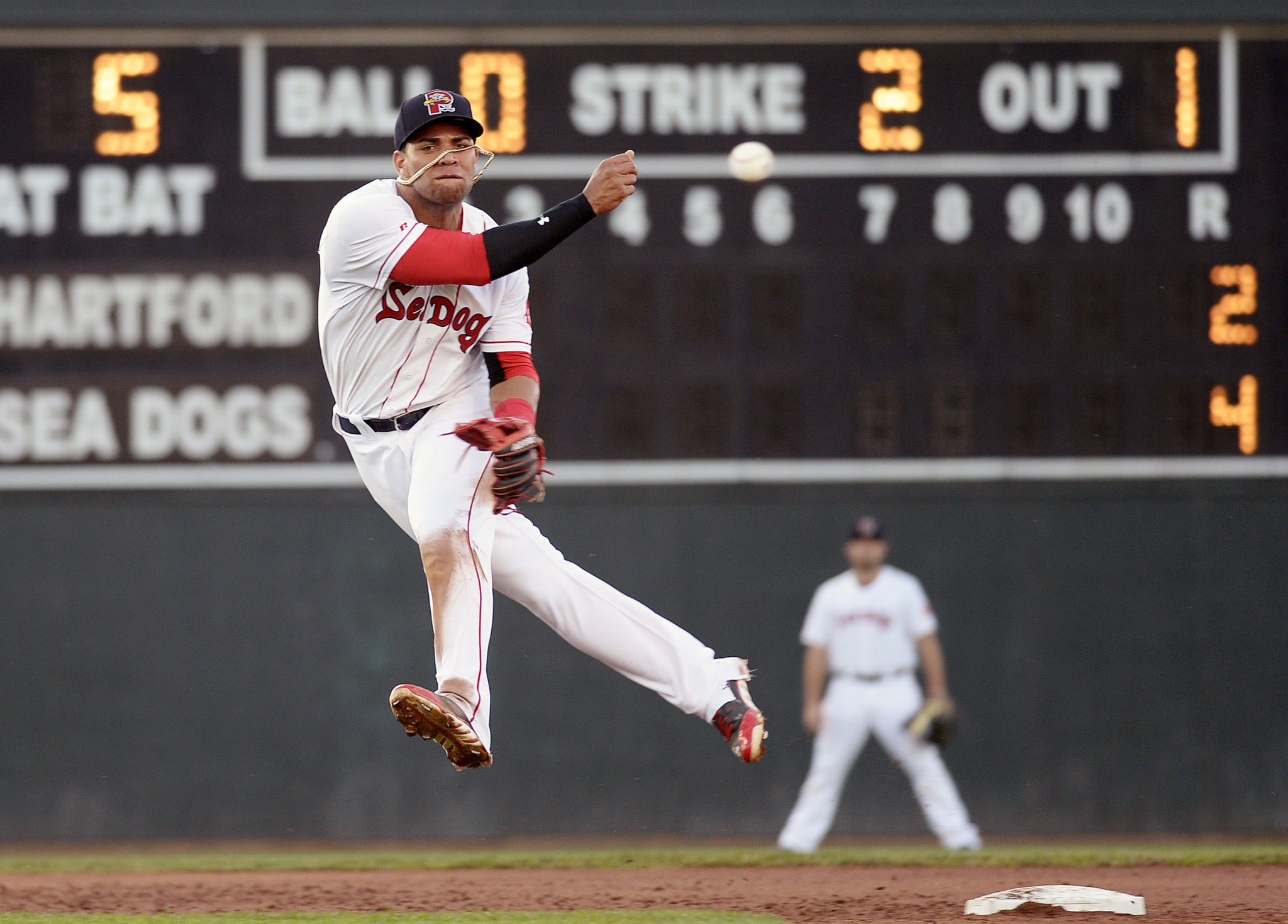

<figcaption>Yoan Moncada’s path to the Red Sox started on Feb. 25, 2015. (Getty)</figcaption></figure>Freedom is a 1.8-ounce piece of sponge cake with a cream filling. It is too many sprays of cologne. It is a washer and dryer. It is everything the teenage boy did not know, did not understand, when he left Cuba and arrived in the United States with an ability to play baseball that inspired a bidding war like none seen before.

Yoan Moncada is finally here, officially with the Boston Red Sox, ready to fulfill a promise he made last year. It was February, and he sat in a restaurant at Southwest Florida International Airport, polishing off a filet mignon and a hamburger, each well-done enough to resemble a hockey puck. Ninety minutes later he would hop on a flight to Boston to sign a $31.5 million contract with the Red Sox, who so adored Moncada they were willing to pay a $31.5 million penalty on top of the salary for exceeding international spending limits.

Getting to that point had taken nearly 21 months of navigating the byzantine laws that allowed Moncada to leave Cuba legally, unlike every other star baseball player smuggled from the island. Moncada had hopped countries, landed in Guatemala, stayed in a hidden location with armed guards, made his way to the United States, thrilled teams in workouts and found himself waiting for Dave and Jo Hastings – a St. Petersburg, Fla.-based CPA and restaurant owner who served as his agents and stewards and proxy parents – to figure out where he was going to play.

Forty-eight hours before the flight, Moncada was at Habana Café, the restaurant Jo runs, leaning up against an island in the kitchen. Jo and Carlos Mesa, an older Cuban player who had served as Moncada’s mentor and confidant, sat nearby. Dave Hastings was in the final stages of negotiations. Teams had streamed in and out of the restaurant the previous month making their pitches. The

San Diego Padres wanted to give Moncada a shot at going right to the major leagues as a teenager. Other teams pushed hard. Ultimately, it came down to the most classic of baseball matchups: Red Sox vs. Yankees.

New York wanted Moncada at $25 million. Hastings said another team was over $30 million. The Yankees refused to budge. Hastings said Moncada would go elsewhere. The Yankees pulled their offer. Hastings called Eddie Romero, the Red Sox’s VP of international scouting, and said: “We’ve got a deal.” Just like that, over the course of two minutes, a 6-foot-2, 205-pound, switch-hitting infielder with game-breaking speed, legitimate power and a jeweler’s eye went from being convinced he was a Yankee – “I really thought that’s where I’d end up,” Moncada said – to the Red Sox.

Moncada, Hastings and Mesa started high-fiving. Jo sat off to the side, quiet. They stopped celebrating and looked at her. Jo was never quiet. They wanted to know what was wrong. Nothing, she said. It’s great. She just … it was surreal.

“I feel numb,” she said.

Silence permeated the kitchen until Moncada broke it.

“And I,” he said, “feel rich.”

They all laughed and spent the next two days preparing to head to Boston and make the deal official. During that time, the future crystallized for Moncada. Even if he was playing second base,

Dustin Pedroia’s position, and even if the Red Sox’s roster burst with enough big-salaried players to keep him buried in the minor leagues for years, Moncada refused to resign himself. Maybe it was the hubris of a 19-year-old, maybe the self-assuredness of someone who believes he’s destined for greatness, but when Moncada finished that steak and burger on Feb. 25, 2015, he vowed his next trip to Fenway Park after signing would be sooner than later.

“Next year,” Moncada said. “I tell myself I’m going to be there next year.”

<center>***</center>

Nothing brought Yoan Moncada, a teenage boy stuck inside a man’s body, quite the satisfaction of a Twinkie. He never could limit himself to one. Or two. He wolfed them down like a snake eating its prey whole. This may sound like an exaggeration, and it may be apocryphal, but those closest to Moncada swear it’s true: One time, over the course of one week, he ate 225 Twinkies. <figure><figure class="cover get-lbdata-from-dom go-to-slideshow-lightbox" data-orig-index="1"> View gallery

.

</figure>

<figcaption>Yoan Moncada’s appetite is as big as his game. (Getty)</figcaption></figure>Moncada will eat just about anything. On Thanksgiving in 2014, the Hastingses hosted a party for about 100 people. On the island in their kitchen sat cookies, candy, cakes, all sorts of sweets, and to keep ants away, they set bright-colored boric-acid traps. Moncada thought it was liquid candy and tried to eat it before screams of “No!” caused him to drop it. This wasn’t the first time Moncada mistook a household item for food. He once tried to ingest a berry-scented liquid air freshener, too.

Before he shipped off to the Red Sox and started to live the life of a baseball player, Moncada needed to learn an entirely new culture as he transitioned to adulthood. The process was painful at times. When he was learning to do laundry, Moncada used an entire box of dryer sheets instead of just one. Before his workouts with teams, he would empty what smelled like half a bottle of cologne on himself, enough that on the drive over, the Hastingses would crack a window just to de-fumigate the car.

Teams weren’t as concerned about the little adjustments as they were other stories about Moncada. No one understood how he got out legally. Rumors persisted about a romantic relationship with an agent and a child. Eventually, teams learned the truth. A woman named Nicole Banks, who had worked at an agency helping secure residency for Cuban players, met Moncada at an international tournament in Rotterdam, where scouts started to recognize he was a potential superstar. Banks later became pregnant with Moncada’s child – a factor that facilitated his legal exit from Cuba – and together they had a son, Robinson, named after Moncada’s favorite player, Robinson Cano.

Most teams’ character concerns vanished when they met Moncada. They saw a kid the same age as recent high school graduates staring at tens of millions of dollars in a new country where he could say what he wanted and do what he wanted and crush 225 Twinkies if he wanted, and that would overwhelm even the most well-adjusted person.

When Moncada received his first check from the Red Sox, he gawked. It wasn’t just all the numbers, the commas. He made $4 a month in Cuba. Four dollars. And here he was, staring at so much money the color started to drain from his face and he turned pale and started sweating. And it wasn’t him being silly or dramatic. Yoan Moncada just couldn’t believe it was real.

<center>***</center>

On the night he flew into Boston, Yoan Moncada saw snow for the first time. Jo Hastings had warned him that where there is snow, there must be snow angels, and so it went: The $63 million kid, on his back in the middle of Boston, flapping his arms and legs and leaving the first imprint of many on the city. The Red Sox paid as much as they did for Moncada because they believe he’s going to be great, though they believed the same in their $72.5 million investment in Rusney Castillo, and the Diamondbacks believed the same in their $68.5 million investment in Yasmany Tomas, and the Dodgers believed the same in their $62.5 million investment in Hector Olivera. To group Moncada with them purely because he resides from the same country, though, is folly. He is an altogether different player than each – a different player than most, really.

<figure><figure class="cover get-lbdata-from-dom go-to-slideshow-lightbox" data-orig-index="2"> View gallery

.

</figure>

<figcaption>It’s unknown how much playing time Yoan Moncada will get with the Red Sox down the stretch. (Getty)</figcaption></figure>Heresy though it may be, one scout who has seen Moncada extensively called him a “poor-man’s Mike Trout,” which is about the finest poor-man comparison one can get. Their bodies are similar – more linebacker than baseball player – and each comes with an enviable power-speed combination. Moncada strikes out too much, certainly – more than a quarter of his plate appearances between High-A and Double-A this year – but his 72 walks rank among the top 20 in all the minor leagues this season, and his slugging percentage ticked up about .500 after his promotion from Salem to Portland.

Just how much of an opportunity he’ll get with Boston isn’t yet clear, even with the third-base job there for the taking. He felt comfortable signing with the Red Sox in part because of how well they treated him. Before his workout, they cobbled together a video of him playing at a tournament in Taipei and games in Cuba and showed it on the stadium’s video screen to say: We’ve wanted you for a long time. The first time he met with the Red Sox, they made sure Luis Tiant, the legendary Cuban pitcher, was there to introduce himself. Between Romero and then-Red Sox general manager Ben Cherington, Boston’s full-court press sold itself, and the investment is looking far better than the disaster that was Castillo.

Whether Moncada, now 21, distinguishes himself immediately remains up to him, though baseball always has felt like the easy part. After Moncada decided he wanted to go to the United States and got the blessing from Iday Abreu, his manager for Cienfuegos in Cuba, he needed to petition INDER, the central sports association in Cuba. He tried calling. Nothing. He drove about three hours, from Cienfuegos to Havana. No luck. Moncada never relented. He wanted to come to the United States, and he didn’t want to do it under the thumb of smugglers and the gangs that run them.

And with the help of a lawyer and a dedicated couple in Florida and a best friend and a woman and a son and an organization that paid twice as much for him as for any amateur before or since, here he is, in Oakland for three days, then San Diego for three more and Toronto for three after that before he gets to go back to Boston. He’ll go there without Twinkie wrappers littering the floor and with a little less eau de parfum and with a better grasp on laundry etiquette. And he’ll go there having fulfilled a promise to himself and ready to fulfill the promise nobody can deny.