Gregg Allman, a founding member of the Allman Brothers Band, the incendiary group that inspired and gave shape to both the Southern rock and jam-band movements, died on Saturday at his home in Savannah, Ga. He was 69.

His death was announced in a statement on Mr. Allman’s official website. No cause was given, but the statement said he had “struggled with many health issues over the past several years.”

The band’s lead singer and keyboardist, Mr. Allman was one of the principal architects of a taut, improvisatory fusion of blues, jazz, country and rock that — streamlined by inheritors like Lynyrd Skynyrd and the Marshall Tucker Band — became the Southern rock of the 1970s.

The group, which originally featured Mr. Allman’s older brother, Duane, on lead and slide guitar, was also a precursor to a generation of popular jam bands, like Widespread Panic and Phish, whose music features labyrinthine instrumental exchanges.

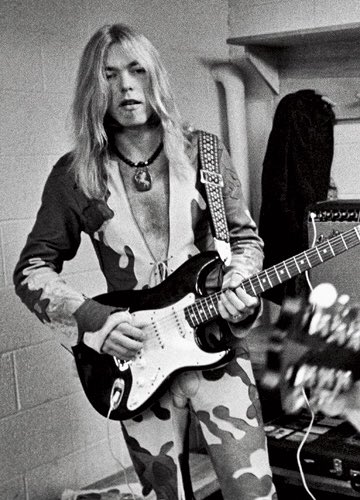

<figure id="media-100000004991632" class="media photo embedded layout-large-horizontal media-100000004991632 ratio-tall" data-media-action="modal" itemprop="associatedMedia" itemscope="" itemid="https://static01.nyt.com/images/2017/05/28/us/allman-obit-1/allman-obit-2-master675.jpg" itemtype="http://schema.org/ImageObject" aria-label="media" role="group" style="display: flex; margin: 45px 0px; position: relative; flex-direction: column; clear: both; max-width: none; width: 645px;">Photo

<figcaption class="caption" itemprop="caption description" style="font-size: 0.8125rem; line-height: 1.0625rem; font-family: nyt-cheltenham-sh, georgia, "times new roman", times, serif; color: rgb(102, 102, 102); max-width: 100%; margin-left: 0px; margin-right: 0px;">From left, Duane Allman, Dickey Betts, Gregg Allman, Jai Johanny Johanson, Berry Oakley and Butch Trucks in 1969. CreditMichael Ochs Archives/Getty Images</figcaption></figure>Mr. Allman’s percussive Hammond B-3 organ playing helped anchor the Allman Brothers’ rhythm section and provided a chuffing counterpoint to the often heated musical interplay between his brother and the band’s other lead guitarist, Dickey Betts.

Continue reading the main story

<aside class="marginalia related-combined-coverage-marginalia marginalia-item nocontent robots-nocontent" data-marginalia-type="sprinkled" role="complementary" module="Related-CombinedMarginalia" style="width: 360px; margin-bottom: 0px; border-top: none; padding-top: 0px; flex-shrink: 0; margin-top: 75px;"><header>RELATED COVERAGE

</header>

</aside>

His vocals, by turns squalling and brooding, took their cue from the anguished emoting of down-home blues singers like Elmore James, as well as more sophisticated ones like Bobby Bland. Foremost among Mr. Allman’s influences as a vocalist, though, was the Mississippi-born blues and soul singer and guitarist known as Little Milton.

“ ‘Little Milton’ Campbell had the strongest set of pipes I ever heard on a human being,” Mr. Allman wrote in his autobiography, “My Cross to Bear,” written with Alan Light (2012). “That man inspired me all my life to get my voice crisper, get my diaphragm harder, use less air and just spit it out. He taught me to be absolutely sure of every note you hit, and to hit it solid.”

The band’s main songwriter early on, Mr. Allman contributed expansive, emotionally fraught compositions like “Dreams” and “Whipping Post” to the Allman Brothers repertoire. Both songs became staples of their epic live shows; a cathartic 22-minute version of “Whipping Post” was a highlight of their acclaimed 1971 live album, “At Fillmore East.”

<figure id="media-100000004991631" class="media photo embedded layout-large-horizontal media-100000004991631 ratio-tall" data-media-action="modal" itemprop="associatedMedia" itemscope="" itemid="https://static01.nyt.com/images/2017/05/28/us/allman-obit-3/allman-obit-3-master675.jpg" itemtype="http://schema.org/ImageObject" aria-label="media" role="group" style="display: flex; margin: 45px 0px; position: relative; flex-direction: column; clear: both; max-width: none; width: 645px;">Photo

<figcaption class="caption" itemprop="caption description" style="font-size: 0.8125rem; line-height: 1.0625rem; font-family: nyt-cheltenham-sh, georgia, "times new roman", times, serif; color: rgb(102, 102, 102); max-width: 100%; margin-left: 0px; margin-right: 0px;">In 1977, Mr. Allman and the singer Cher, who were then married, performed in Brussels on tour for their album, “Two the Hard Way.” The project was poorly received by critics and the record-buying public alike. CreditBettmann</figcaption></figure>More concise originals like “Midnight Rider” and “Melissa,” as well as Mr. Allman’s renditions of blues classics like “Statesboro Blues” and “Done Somebody Wrong,” revealed his singular affinity with the black Southern musical vernacular.

Mr. Allman also enjoyed an enduring, if intermittent, career as a solo artist, both while a member of the Allman Brothers Band and during periods when he was away from the group. His recordings under his own name were typically more subdued, more akin to soulful singer-songwriter rock, than his molten performances with the Allmans.

A remake of “Midnight Rider” from “Laid Back,” his first solo album, reached the pop Top 20 in 1973. “Laid Back” also featured a cover of “These Days,” an elegiac ballad written by Jackson Browne, who on occasion roomed with Mr. Allman while he was living in Los Angeles in the 1960s.

“Low Country Blues,” Mr. Allman’s sixth studio recording as a solo artist, was nominated for a Grammy Award for best blues album in 2011. Produced by T Bone Burnett, it consisted largely of interpretations of blues standards made popular by performers like Junior Wells and Muddy Waters.

https://www.nytimes.com/2017/05/27/arts/music/gregg-allman-dead-allman-brothers-band.html?_r=0

His death was announced in a statement on Mr. Allman’s official website. No cause was given, but the statement said he had “struggled with many health issues over the past several years.”

The band’s lead singer and keyboardist, Mr. Allman was one of the principal architects of a taut, improvisatory fusion of blues, jazz, country and rock that — streamlined by inheritors like Lynyrd Skynyrd and the Marshall Tucker Band — became the Southern rock of the 1970s.

The group, which originally featured Mr. Allman’s older brother, Duane, on lead and slide guitar, was also a precursor to a generation of popular jam bands, like Widespread Panic and Phish, whose music features labyrinthine instrumental exchanges.

<figure id="media-100000004991632" class="media photo embedded layout-large-horizontal media-100000004991632 ratio-tall" data-media-action="modal" itemprop="associatedMedia" itemscope="" itemid="https://static01.nyt.com/images/2017/05/28/us/allman-obit-1/allman-obit-2-master675.jpg" itemtype="http://schema.org/ImageObject" aria-label="media" role="group" style="display: flex; margin: 45px 0px; position: relative; flex-direction: column; clear: both; max-width: none; width: 645px;">Photo

<figcaption class="caption" itemprop="caption description" style="font-size: 0.8125rem; line-height: 1.0625rem; font-family: nyt-cheltenham-sh, georgia, "times new roman", times, serif; color: rgb(102, 102, 102); max-width: 100%; margin-left: 0px; margin-right: 0px;">From left, Duane Allman, Dickey Betts, Gregg Allman, Jai Johanny Johanson, Berry Oakley and Butch Trucks in 1969. CreditMichael Ochs Archives/Getty Images</figcaption></figure>Mr. Allman’s percussive Hammond B-3 organ playing helped anchor the Allman Brothers’ rhythm section and provided a chuffing counterpoint to the often heated musical interplay between his brother and the band’s other lead guitarist, Dickey Betts.

Continue reading the main story

<aside class="marginalia related-combined-coverage-marginalia marginalia-item nocontent robots-nocontent" data-marginalia-type="sprinkled" role="complementary" module="Related-CombinedMarginalia" style="width: 360px; margin-bottom: 0px; border-top: none; padding-top: 0px; flex-shrink: 0; margin-top: 75px;"><header>RELATED COVERAGE

</header>

- <article class="story theme-summary ">

BOOKS OF THE TIMES

‘My Cross to Bear,’ Gregg Allman’s Memoir<time class="dateline" style="font-size: 0.625rem; line-height: 1.0625rem; font-family: nyt-franklin, arial, helvetica, sans-serif; color: rgb(153, 153, 153); white-space: nowrap; display: inline-block;">MAY 27, 2012</time>

</article> - <article class="story theme-summary ">

MUSIC REVIEW

The Allman Brothers Band at Beacon Theater <time class="dateline" style="font-size: 0.625rem; line-height: 1.0625rem; font-family: nyt-franklin, arial, helvetica, sans-serif; color: rgb(153, 153, 153); white-space: nowrap; display: inline-block;">MARCH 8, 2014</time>

</article>

</aside>

His vocals, by turns squalling and brooding, took their cue from the anguished emoting of down-home blues singers like Elmore James, as well as more sophisticated ones like Bobby Bland. Foremost among Mr. Allman’s influences as a vocalist, though, was the Mississippi-born blues and soul singer and guitarist known as Little Milton.

“ ‘Little Milton’ Campbell had the strongest set of pipes I ever heard on a human being,” Mr. Allman wrote in his autobiography, “My Cross to Bear,” written with Alan Light (2012). “That man inspired me all my life to get my voice crisper, get my diaphragm harder, use less air and just spit it out. He taught me to be absolutely sure of every note you hit, and to hit it solid.”

The band’s main songwriter early on, Mr. Allman contributed expansive, emotionally fraught compositions like “Dreams” and “Whipping Post” to the Allman Brothers repertoire. Both songs became staples of their epic live shows; a cathartic 22-minute version of “Whipping Post” was a highlight of their acclaimed 1971 live album, “At Fillmore East.”

<figure id="media-100000004991631" class="media photo embedded layout-large-horizontal media-100000004991631 ratio-tall" data-media-action="modal" itemprop="associatedMedia" itemscope="" itemid="https://static01.nyt.com/images/2017/05/28/us/allman-obit-3/allman-obit-3-master675.jpg" itemtype="http://schema.org/ImageObject" aria-label="media" role="group" style="display: flex; margin: 45px 0px; position: relative; flex-direction: column; clear: both; max-width: none; width: 645px;">Photo

<figcaption class="caption" itemprop="caption description" style="font-size: 0.8125rem; line-height: 1.0625rem; font-family: nyt-cheltenham-sh, georgia, "times new roman", times, serif; color: rgb(102, 102, 102); max-width: 100%; margin-left: 0px; margin-right: 0px;">In 1977, Mr. Allman and the singer Cher, who were then married, performed in Brussels on tour for their album, “Two the Hard Way.” The project was poorly received by critics and the record-buying public alike. CreditBettmann</figcaption></figure>More concise originals like “Midnight Rider” and “Melissa,” as well as Mr. Allman’s renditions of blues classics like “Statesboro Blues” and “Done Somebody Wrong,” revealed his singular affinity with the black Southern musical vernacular.

Mr. Allman also enjoyed an enduring, if intermittent, career as a solo artist, both while a member of the Allman Brothers Band and during periods when he was away from the group. His recordings under his own name were typically more subdued, more akin to soulful singer-songwriter rock, than his molten performances with the Allmans.

A remake of “Midnight Rider” from “Laid Back,” his first solo album, reached the pop Top 20 in 1973. “Laid Back” also featured a cover of “These Days,” an elegiac ballad written by Jackson Browne, who on occasion roomed with Mr. Allman while he was living in Los Angeles in the 1960s.

“Low Country Blues,” Mr. Allman’s sixth studio recording as a solo artist, was nominated for a Grammy Award for best blues album in 2011. Produced by T Bone Burnett, it consisted largely of interpretations of blues standards made popular by performers like Junior Wells and Muddy Waters.

https://www.nytimes.com/2017/05/27/arts/music/gregg-allman-dead-allman-brothers-band.html?_r=0