You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

For four decades, other gamblers have tried to be Billy Walters while investigators have tried to bring him down. And for four decades, the world's mo

- Thread starter Akillies

- Start date

ESPN The Magazine

by Mike FishILLUSTRATIONS BY ALEXANDER WELLS

<time>02/06/15</time>

<hgroup></hgroup>[h=4]More from The Mag's Gambling Issue[/h]Purdum: Silver's stand on gambling | Video

ESPN The Mag: Wagering on the future

Staff: Gambling confidential

Chalk Home »

ON A MID-SEPTEMBER night, Ezekiel Rubalcada swaggers through the doors of Las Vegas' M Resort Spa Casino. He moves to the half-moon-shaped bar overlooking the sportsbook, catching up with old friends. He exchanges high-fives and playful F-bombs with a couple of bartenders, then makes a raunchy pass at a brunette waitress who escapes in a near sprint.

For 38-year-old Rubalcada, being at the M is a pleasing trip down memory lane, a visit to his primary workplace throughout 2010 and 2011. Back then, he had nearly $1 million in his account at the M. Dressed in slacks and a sport coat, he would saunter in and bet six figures a week on NFL and college games. He was, M Resort staffers say, one of the sportsbook's "bigger guys" -- a high roller who could afford to bet very, very big.

But he wasn't that at all.

In fact, Rubalcada was a faceless grunt in the most succ essful gambling enterprise of all time. The divorced father of two says he was paid $1,200 a week by an outfit called ACME Group Trading to sip vodka tonics or Bud Lights until a man he'd never met called or texted him on his small Nokia phone. The voice would tell Rubalcada, known as Lubbock, how many thousands of dollars to place on which games -- immediately. But the ultimate orders came from the greatest and most controversial sports gambler ever: William T. "Billy" Walters.

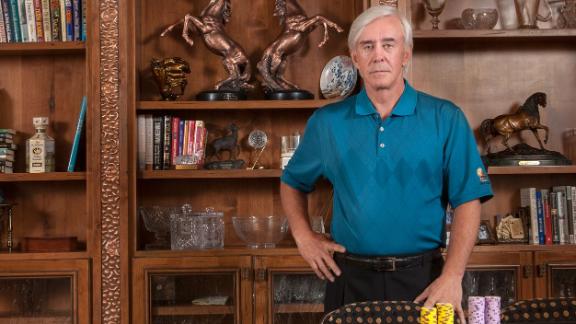

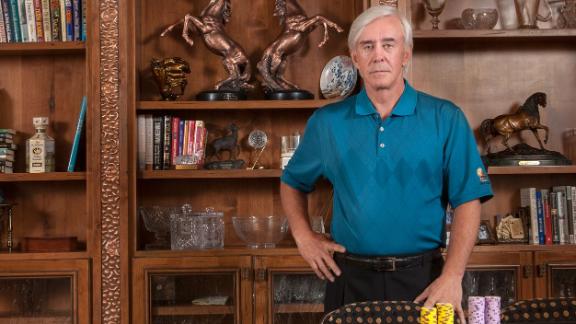

For almost four decades, Walters, now 68, is thought to have bet more money more successfully than anyone in history, earning hundreds of millions of dollars. Federal and state investigators sniff around his operation regularly. Scores of bettors and bookies have tried to crack his methods so they can emulate him. Even Walters' employees, like Rubalcada, have tried to figure him out so they can win alongside him. Walters has outrun them all.

What's clear, according to dozens of interviews and thousands of pages of legal documents, is that Walters beats the odds everywhere -- in the stock market, real estate, criminal proceedings and his true wheelhouse, sports gambling. His talent brought him from a life of poverty in rural Kentucky to one of wild success. He owns a fleet of car dealerships, several high-end golf courses, a private jet and fabulous homes in places like Palm Desert and Cabo San Lucas.

by Mike FishILLUSTRATIONS BY ALEXANDER WELLS

<time>02/06/15</time>

<hgroup></hgroup>[h=4]More from The Mag's Gambling Issue[/h]Purdum: Silver's stand on gambling | Video

ESPN The Mag: Wagering on the future

Staff: Gambling confidential

Chalk Home »

ON A MID-SEPTEMBER night, Ezekiel Rubalcada swaggers through the doors of Las Vegas' M Resort Spa Casino. He moves to the half-moon-shaped bar overlooking the sportsbook, catching up with old friends. He exchanges high-fives and playful F-bombs with a couple of bartenders, then makes a raunchy pass at a brunette waitress who escapes in a near sprint.

For 38-year-old Rubalcada, being at the M is a pleasing trip down memory lane, a visit to his primary workplace throughout 2010 and 2011. Back then, he had nearly $1 million in his account at the M. Dressed in slacks and a sport coat, he would saunter in and bet six figures a week on NFL and college games. He was, M Resort staffers say, one of the sportsbook's "bigger guys" -- a high roller who could afford to bet very, very big.

But he wasn't that at all.

In fact, Rubalcada was a faceless grunt in the most succ essful gambling enterprise of all time. The divorced father of two says he was paid $1,200 a week by an outfit called ACME Group Trading to sip vodka tonics or Bud Lights until a man he'd never met called or texted him on his small Nokia phone. The voice would tell Rubalcada, known as Lubbock, how many thousands of dollars to place on which games -- immediately. But the ultimate orders came from the greatest and most controversial sports gambler ever: William T. "Billy" Walters.

For almost four decades, Walters, now 68, is thought to have bet more money more successfully than anyone in history, earning hundreds of millions of dollars. Federal and state investigators sniff around his operation regularly. Scores of bettors and bookies have tried to crack his methods so they can emulate him. Even Walters' employees, like Rubalcada, have tried to figure him out so they can win alongside him. Walters has outrun them all.

What's clear, according to dozens of interviews and thousands of pages of legal documents, is that Walters beats the odds everywhere -- in the stock market, real estate, criminal proceedings and his true wheelhouse, sports gambling. His talent brought him from a life of poverty in rural Kentucky to one of wild success. He owns a fleet of car dealerships, several high-end golf courses, a private jet and fabulous homes in places like Palm Desert and Cabo San Lucas.

Walters, according to interviews, is both kind and a bully, charming and scheming. He maintains an opulent lifestyle but also gives lavishly to charity as well as to presidents, governors and city council members. Among everyone who knows him -- from employees to bookmakers to politicians and investigators -- he elicits admiration, fear, jealousy and consternation in nearly equal measures.

Inside The World Of Sports GamblingJohn Mastronardo discusses his relationship with Billy Walters, one of the most successful sports gamblers ever.

Inside The World Of Sports GamblingJohn Mastronardo discusses his relationship with Billy Walters, one of the most successful sports gamblers ever.

WALTERS DOESN'T WANT to talk much about any of it. Over a period of several months, he begs off numerous interview requests from ESPN, saying his lawyers want him to keep quiet because of the latest investigation against him. Last spring his name appeared in headlines next to those of pro golfer Phil Mickelson -- a friend and occasional golf partner -- and billionaire investor Carl Icahn as targets of a federal insider-trading investigation. Walters has denied wrongdoing, but the case remains open.

In one phone call, he rails about his distrust of the media. Another call ends with a referral to his attorney. In late January, he answers a few questions and agrees to a fuller interview if ESPN agrees not to ask him about the insider-trading case or write about allegations that he once provided information to an FBI agent. ESPN declines the offer.

Walters repeatedly voices frustration over what he says are draconian laws that drive a massive market of betting dollars to poorly regulated offshore locales. "Why don't we license this thing?" Walters says. "Why don't we regulate it? Why don't we keep the bad guys out? Why don't we generate some jobs?

"Everybody in this country bets on sports," he continues. "If you were to take away the office pools, fantasy pools, people betting on sports, I guarantee the [TV] viewership would be cut in less than half."

"It was scrupulously set up, better set up legally than your average business."

<cite>- Brian Rutledge</cite>

Even when there isn't an FBI investigation looming, Walters isn't willing to talk much about his work. One of the few times he got close -- in a fawning 60 Minutes profile in 2011 -- he spoke only in general terms. He's been more open about his background: He was born to a poor teenage mother in southern Kentucky and raised primarily by his grandmother until she died when Billy was 12. He started placing bets as a young boy and lost all his savings -- $75 -- betting on the New York Yankees against the Brooklyn Dodgers in the '55 World Series. In the early 1980s, he left two failed marriages and a car salesman gig behind in Kentucky and, after a misdemeanor gambling conviction, headed west with a tiny bank account and a heavy drinking habit.

After arriving in Vegas, Walters connected with the people who would help him turn his gambling habit into a career. In 1980, Dr. Ivan Mindlin and Michael Kent had formed the now-legendary Computer Group, which pioneered the use of computer algorithms for sports betting. Mindlin was the self-indulgent frontman, a surgeon-turned-gambler. The technology was run by Kent, a mathematician who developed nuclear submarine technology. By the early '80s, the Computer Group had burgeoned into the first national network of sports bettors, betting hundreds of thousands a day. The collective's gamblers, handicappers and investors began earning millions.

Walters was inexperienced, but Mindlin was impressed with his moxie and recommended his hiring to Kent in 1983. Walters was tasked with exploiting the weakest betting lines with bookies, then eventually with moving millions every week in exchange for a cut of the profits. "I gave birth to him," Mindlin says.

After a few years, Walters quit drinking for good and morphed into a member of Las Vegas' influential elite, developing golf courses, subdivisions and industrial parks. According to Jack Sheehan, a longtime Vegas pal, Walters fancies himself an across-the-board genius whose business acumen stretches far beyond betting. He prefers being seen as a successful entrepreneur, the friend says, not just a "Las Vegas gambler." Walters says sports betting now occupies less than 7 percent of his time.

But gambling was how he made his name. "I can tell you nobody has ever approached sports betting with as much analysis, as much technical capability, computer analysis," says Sheehan, who is writing a biography on Walters. "And he has a work ethic that is just ridiculous. If you and I had $300 million, we might play golf five days a week. Or be on a beach with three gals in bikinis. Billy works as hard today as he did when he was a used-car salesman in Kentucky."

Inside The World Of Sports GamblingJohn Mastronardo discusses his relationship with Billy Walters, one of the most successful sports gamblers ever.

Inside The World Of Sports GamblingJohn Mastronardo discusses his relationship with Billy Walters, one of the most successful sports gamblers ever.WALTERS DOESN'T WANT to talk much about any of it. Over a period of several months, he begs off numerous interview requests from ESPN, saying his lawyers want him to keep quiet because of the latest investigation against him. Last spring his name appeared in headlines next to those of pro golfer Phil Mickelson -- a friend and occasional golf partner -- and billionaire investor Carl Icahn as targets of a federal insider-trading investigation. Walters has denied wrongdoing, but the case remains open.

In one phone call, he rails about his distrust of the media. Another call ends with a referral to his attorney. In late January, he answers a few questions and agrees to a fuller interview if ESPN agrees not to ask him about the insider-trading case or write about allegations that he once provided information to an FBI agent. ESPN declines the offer.

Walters repeatedly voices frustration over what he says are draconian laws that drive a massive market of betting dollars to poorly regulated offshore locales. "Why don't we license this thing?" Walters says. "Why don't we regulate it? Why don't we keep the bad guys out? Why don't we generate some jobs?

"Everybody in this country bets on sports," he continues. "If you were to take away the office pools, fantasy pools, people betting on sports, I guarantee the [TV] viewership would be cut in less than half."

"It was scrupulously set up, better set up legally than your average business."

<cite>- Brian Rutledge</cite>

Even when there isn't an FBI investigation looming, Walters isn't willing to talk much about his work. One of the few times he got close -- in a fawning 60 Minutes profile in 2011 -- he spoke only in general terms. He's been more open about his background: He was born to a poor teenage mother in southern Kentucky and raised primarily by his grandmother until she died when Billy was 12. He started placing bets as a young boy and lost all his savings -- $75 -- betting on the New York Yankees against the Brooklyn Dodgers in the '55 World Series. In the early 1980s, he left two failed marriages and a car salesman gig behind in Kentucky and, after a misdemeanor gambling conviction, headed west with a tiny bank account and a heavy drinking habit.

After arriving in Vegas, Walters connected with the people who would help him turn his gambling habit into a career. In 1980, Dr. Ivan Mindlin and Michael Kent had formed the now-legendary Computer Group, which pioneered the use of computer algorithms for sports betting. Mindlin was the self-indulgent frontman, a surgeon-turned-gambler. The technology was run by Kent, a mathematician who developed nuclear submarine technology. By the early '80s, the Computer Group had burgeoned into the first national network of sports bettors, betting hundreds of thousands a day. The collective's gamblers, handicappers and investors began earning millions.

Walters was inexperienced, but Mindlin was impressed with his moxie and recommended his hiring to Kent in 1983. Walters was tasked with exploiting the weakest betting lines with bookies, then eventually with moving millions every week in exchange for a cut of the profits. "I gave birth to him," Mindlin says.

After a few years, Walters quit drinking for good and morphed into a member of Las Vegas' influential elite, developing golf courses, subdivisions and industrial parks. According to Jack Sheehan, a longtime Vegas pal, Walters fancies himself an across-the-board genius whose business acumen stretches far beyond betting. He prefers being seen as a successful entrepreneur, the friend says, not just a "Las Vegas gambler." Walters says sports betting now occupies less than 7 percent of his time.

But gambling was how he made his name. "I can tell you nobody has ever approached sports betting with as much analysis, as much technical capability, computer analysis," says Sheehan, who is writing a biography on Walters. "And he has a work ethic that is just ridiculous. If you and I had $300 million, we might play golf five days a week. Or be on a beach with three gals in bikinis. Billy works as hard today as he did when he was a used-car salesman in Kentucky."

RUBALCADA HAD everyone fooled.

Walters' big action is unwelcome in many sportsbooks in Vegas, so he relies on his network of "runners" like Rubalcada, who are tasked with placing bets without giving any hint that they're working for someone else.

"When I was first introduced to [Walters], he told me, 'This is the first and the last time you'll ever see me,'" Rubalcada says. "He was like, 'If they see you with me, you are no good to me.'"

Vegas sportsbooks fear losing huge to top gamblers, so many set limits of $10,000 on college and $20,000 on NFL games. Meanwhile, an account that's too successful runs the risk of being shut down. That makes a large network a major advantage -- each runner stays under the limit, but the total amount bet on Walters' behalf often exceeds it many times over.

"There are some groups out there that bet an awful lot of money, but they don't do it at anywhere near the sophistication," says David Malinsky, a longtime handicapper who says he previously worked for Walters evaluating teams and analyzing games. "They can put the network together of picking the games and having the handicappers. But they can't build out that distribution network."

So Rubalcada spent day after day in the dimly lit sportsbook, waiting to hear from a guy nicknamed Wolf, whose urgent messages would arrive shortly before kickoff or tip-off. Rubalcada would instantly punch in bets on an M Resort tablet linked to his account.

"He never came across like he was betting for Billy or anybody else," says Mike Miller, the M's former risk management supervisor. "He was acting like it was all his money."

But in fact, Rubalcada wasn't even always trying to win, though he didn't know it at the time. Eventually, he grew to understand one of Walters' keys to success: Some of his bets were intentional losers, designed to manipulate the bookmakers' odds. Walters might bet $50,000 on a team giving 3 points, then $75,000 more on the same team when the line reaches 3.5. The moment the line gets to 4, a runner is instructed to immediately place a larger bet -- perhaps $250,000 -- on the other team. The $125,000 on the initial lines will be lost, but if things go according to plan, the $250,000 on the other side will win enough to make up for it many times over. Walters uses the same method on multiple games, often risking millions each weekend.

Since the days of the Computer Group, analytically inclined professional gamblers have relied on technology as well as research to produce what is called a delta: the difference between the Vegas line and what the bettors conclude the point spread should be. The greater the delta, the more money a gambler like Walters will bet. There's nothing illegal about manipulating lines, and many prominent gamblers have the ability to move a line with as little as $1,000. Walters' strategy is simply more sophisticated and uses more people, better information and, of course, more dollars bet in far more places than anyone else's, insiders say.

Walters' big action is unwelcome in many sportsbooks in Vegas, so he relies on his network of "runners" like Rubalcada, who are tasked with placing bets without giving any hint that they're working for someone else.

"When I was first introduced to [Walters], he told me, 'This is the first and the last time you'll ever see me,'" Rubalcada says. "He was like, 'If they see you with me, you are no good to me.'"

Vegas sportsbooks fear losing huge to top gamblers, so many set limits of $10,000 on college and $20,000 on NFL games. Meanwhile, an account that's too successful runs the risk of being shut down. That makes a large network a major advantage -- each runner stays under the limit, but the total amount bet on Walters' behalf often exceeds it many times over.

"There are some groups out there that bet an awful lot of money, but they don't do it at anywhere near the sophistication," says David Malinsky, a longtime handicapper who says he previously worked for Walters evaluating teams and analyzing games. "They can put the network together of picking the games and having the handicappers. But they can't build out that distribution network."

So Rubalcada spent day after day in the dimly lit sportsbook, waiting to hear from a guy nicknamed Wolf, whose urgent messages would arrive shortly before kickoff or tip-off. Rubalcada would instantly punch in bets on an M Resort tablet linked to his account.

"He never came across like he was betting for Billy or anybody else," says Mike Miller, the M's former risk management supervisor. "He was acting like it was all his money."

But in fact, Rubalcada wasn't even always trying to win, though he didn't know it at the time. Eventually, he grew to understand one of Walters' keys to success: Some of his bets were intentional losers, designed to manipulate the bookmakers' odds. Walters might bet $50,000 on a team giving 3 points, then $75,000 more on the same team when the line reaches 3.5. The moment the line gets to 4, a runner is instructed to immediately place a larger bet -- perhaps $250,000 -- on the other team. The $125,000 on the initial lines will be lost, but if things go according to plan, the $250,000 on the other side will win enough to make up for it many times over. Walters uses the same method on multiple games, often risking millions each weekend.

Since the days of the Computer Group, analytically inclined professional gamblers have relied on technology as well as research to produce what is called a delta: the difference between the Vegas line and what the bettors conclude the point spread should be. The greater the delta, the more money a gambler like Walters will bet. There's nothing illegal about manipulating lines, and many prominent gamblers have the ability to move a line with as little as $1,000. Walters' strategy is simply more sophisticated and uses more people, better information and, of course, more dollars bet in far more places than anyone else's, insiders say.

The work starts well in advance of a game. Malinsky, who says he worked for Walters on two occasions as a college football handicapper, says he routinely provided Walters quantified evaluations of teams, broken down by color codes and letter grades. Walters had similar arrangements with others who handicapped NFL, NBA and college basketball games.

The vast Walters network also includes a guy on the East Coast known as The Reader, who scans local newspapers, websites, blogs and Twitter for revealing tidbits or injury updates. That information is weighed and plugged into the computer alongside other statistical data -- from field conditions to intricate breakdowns of officiating crews. Armed with algorithms and probability theories, the objective is to find the mispriced team, then hammer the line to where Walters wants it.

"What Billy is also able to do is handicap the handicappers," says Malinsky, now the editor-in-chief of news for Pregame.com, a Vegas-based website selling handicapping information. "So after a while he knows what this type of game from this guy is worth. He will just absorb the information and then make the final decision. He is the coach calling the plays."

Asked about Malinsky's descriptions, Walters says, "He has no clue how my operation runs. Unfortunately, David wasn't successful in what he did, and I discontinued the relationship."

Rubalcada, in his position as a runner, didn't know the details of how any bets came together. Rubalcada says he made his way into Walters' world booking tee times at Royal Links Golf Club, a pricey course Walters owns a few miles off the Strip. Rubalcada says he advanced to a job best described as course hustler, setting up on a par-3 hole with his pitching wedge and offering foursomes the chance to wager on who would make it closest to the pin.

When Walters' gambling operation offered him a job, Rubalcada saw a chance to make huge money. Eventually, he began mimicking some of Walters' betting action with his own funds, relying on an inside source to text whether Walters' bets were real or phony moves. It didn't always work, and Rubalcada dug himself a hole so deep that he began embezzling from his Walters-funded account, taking a total of $482,833. He added to his troubles when he attempted to cover the theft by staging a carjacking, which was captured on hotel video surveillance.

Rubalcada eventually pleaded guilty to two felony theft counts and last March was sentenced to three years' probation and ordered to make restitution of $364,634. "I'll be dead before they get that money back," he says. In the fall, his legal woes escalated when he was jailed for violating the terms of his probation, which included random drug testing and prohibitions on alcohol use and gambling. Rubalcada, who drank heavily during two ESPN interviews, remains in jail awaiting a spot at a drug treatment facility.

After Rubalcada was arrested, one of Walters' attorneys visited the county prosecutor's office -- without prodding -- armed with records detailing how the gambling operation was set up legitimately through a limited liability corporation. The move surprised and impressed authorities, as did the fact that a former Vegas detective was overseeing the group's security arm. "They had one of the biggest law firms in the city set up their entire corporation and their books," says Brian Rutledge, Clark County's chief deputy district attorney. "It was scrupulously set up to be in compliance with all the gaming regulations. They were better set up legally than your average business, let's put it that way."

EVEN THE GREATEST gambler of all time doesn't always win -- but he doesn't have to. In the sports gambling world, where the house takes a 10 percent cut, bettors need to win 52.38 percent of their games to break even. Any additional wins represent pure profit -- and when hundreds of thousands of dollars are wagered on a single game, lots of it.

"The average guy on the street might be disillusioned if he knew the actual winning percentage," Malinsky says of Walters' consistent but seemingly modest success against the line. "What people don't understand is that the difference between winning 53 percent and 55 percent is like swimming the Atlantic Ocean."

Walters gets those extra 2 percentage points and sometimes much more. He has boasted that he has suffered only one losing season in 39 years, and past criminal investigations provide a snapshot of his success. The 1985 raid against the Computer Group revealed that the syndicate won an eye-popping 60.3 percent of its college football picks one season. More recently, an unsuccessful money-laundering case in 2002 found that Walters was consistently winning as much as 58 percent a week, sources told ESPN. This year, Walters says, he expects to break even. "Quite frankly, this may be my last year," he says. "I may not do this anymore."

Another myth about professional gambling is that every big bet is made in Vegas. Placing bets outside Nevada is a legal gray area and, as a result, a subject on which those close to Walters refuse to shed much light. But multiple sources estimate that only a small fraction of Walters' bets are actually placed there. The remainder, they say, happen either at offshore gambling sites or, to a lesser extent, through a network of bookies, many of whom have had relationships with Walters for decades.

Sources say Walters' operation has become more active in offshore sportsbooks, in Europe and in the emerging Asian market. A 1996 raid on Walters' office found more than 40 telephones, from which authorities said more than 12,000 long-distance calls a month were placed to illegal bookmakers in the U.S., Canada, Central America and the Caribbean. Additionally, documents detail a wire transfer of $970,000 -- suspected by authorities at the time of being "illegal gaming winnings" -- into Walters' Las Vegas bank account through banks in Montreal, London and New York. Walters was indicted three times for money laundering in connection with the investigation, but the charges were dropped before trial.

Today, sources say, the headquarters of Walters' international operation is located outside the United States. The last known location was in Panama, according to sources, after earlier offices were based in London, the Bahamas and Tijuana, Mexico. "Very little happens here," one source familiar with Walters' operation says of the group's Vegas-based gambling.

FEW PEOPLE HAVE experienced the many facets of Walters' personality as intimately as John Mastronardo, a convicted gambler and the younger brother of one of the country's biggest bookies. Mastronardo, who says he worked for Walters from 2000 to 2005, calls his former boss a genius. But he also witnessed what he saw as a dark side -- Walters could be cunning and openly malicious, he says.

Mastronardo, who has also dabbled as a bookie and worked in the Caribbean as an offshore sportsbook operator, says he and 20 or so underlings moved bets for Walters from Philadelphia before he moved to Las Vegas to work out of Walters' headquarters in exchange for a 25 percent cut of the winnings. "At times, he would give me $1 million to hold, $2 million to hold, with no signed contract," Mastronardo says. "I was betting it for him, so he staked me a bankroll.

The vast Walters network also includes a guy on the East Coast known as The Reader, who scans local newspapers, websites, blogs and Twitter for revealing tidbits or injury updates. That information is weighed and plugged into the computer alongside other statistical data -- from field conditions to intricate breakdowns of officiating crews. Armed with algorithms and probability theories, the objective is to find the mispriced team, then hammer the line to where Walters wants it.

"What Billy is also able to do is handicap the handicappers," says Malinsky, now the editor-in-chief of news for Pregame.com, a Vegas-based website selling handicapping information. "So after a while he knows what this type of game from this guy is worth. He will just absorb the information and then make the final decision. He is the coach calling the plays."

Asked about Malinsky's descriptions, Walters says, "He has no clue how my operation runs. Unfortunately, David wasn't successful in what he did, and I discontinued the relationship."

Rubalcada, in his position as a runner, didn't know the details of how any bets came together. Rubalcada says he made his way into Walters' world booking tee times at Royal Links Golf Club, a pricey course Walters owns a few miles off the Strip. Rubalcada says he advanced to a job best described as course hustler, setting up on a par-3 hole with his pitching wedge and offering foursomes the chance to wager on who would make it closest to the pin.

When Walters' gambling operation offered him a job, Rubalcada saw a chance to make huge money. Eventually, he began mimicking some of Walters' betting action with his own funds, relying on an inside source to text whether Walters' bets were real or phony moves. It didn't always work, and Rubalcada dug himself a hole so deep that he began embezzling from his Walters-funded account, taking a total of $482,833. He added to his troubles when he attempted to cover the theft by staging a carjacking, which was captured on hotel video surveillance.

Rubalcada eventually pleaded guilty to two felony theft counts and last March was sentenced to three years' probation and ordered to make restitution of $364,634. "I'll be dead before they get that money back," he says. In the fall, his legal woes escalated when he was jailed for violating the terms of his probation, which included random drug testing and prohibitions on alcohol use and gambling. Rubalcada, who drank heavily during two ESPN interviews, remains in jail awaiting a spot at a drug treatment facility.

After Rubalcada was arrested, one of Walters' attorneys visited the county prosecutor's office -- without prodding -- armed with records detailing how the gambling operation was set up legitimately through a limited liability corporation. The move surprised and impressed authorities, as did the fact that a former Vegas detective was overseeing the group's security arm. "They had one of the biggest law firms in the city set up their entire corporation and their books," says Brian Rutledge, Clark County's chief deputy district attorney. "It was scrupulously set up to be in compliance with all the gaming regulations. They were better set up legally than your average business, let's put it that way."

EVEN THE GREATEST gambler of all time doesn't always win -- but he doesn't have to. In the sports gambling world, where the house takes a 10 percent cut, bettors need to win 52.38 percent of their games to break even. Any additional wins represent pure profit -- and when hundreds of thousands of dollars are wagered on a single game, lots of it.

"The average guy on the street might be disillusioned if he knew the actual winning percentage," Malinsky says of Walters' consistent but seemingly modest success against the line. "What people don't understand is that the difference between winning 53 percent and 55 percent is like swimming the Atlantic Ocean."

Walters gets those extra 2 percentage points and sometimes much more. He has boasted that he has suffered only one losing season in 39 years, and past criminal investigations provide a snapshot of his success. The 1985 raid against the Computer Group revealed that the syndicate won an eye-popping 60.3 percent of its college football picks one season. More recently, an unsuccessful money-laundering case in 2002 found that Walters was consistently winning as much as 58 percent a week, sources told ESPN. This year, Walters says, he expects to break even. "Quite frankly, this may be my last year," he says. "I may not do this anymore."

Another myth about professional gambling is that every big bet is made in Vegas. Placing bets outside Nevada is a legal gray area and, as a result, a subject on which those close to Walters refuse to shed much light. But multiple sources estimate that only a small fraction of Walters' bets are actually placed there. The remainder, they say, happen either at offshore gambling sites or, to a lesser extent, through a network of bookies, many of whom have had relationships with Walters for decades.

Sources say Walters' operation has become more active in offshore sportsbooks, in Europe and in the emerging Asian market. A 1996 raid on Walters' office found more than 40 telephones, from which authorities said more than 12,000 long-distance calls a month were placed to illegal bookmakers in the U.S., Canada, Central America and the Caribbean. Additionally, documents detail a wire transfer of $970,000 -- suspected by authorities at the time of being "illegal gaming winnings" -- into Walters' Las Vegas bank account through banks in Montreal, London and New York. Walters was indicted three times for money laundering in connection with the investigation, but the charges were dropped before trial.

Today, sources say, the headquarters of Walters' international operation is located outside the United States. The last known location was in Panama, according to sources, after earlier offices were based in London, the Bahamas and Tijuana, Mexico. "Very little happens here," one source familiar with Walters' operation says of the group's Vegas-based gambling.

FEW PEOPLE HAVE experienced the many facets of Walters' personality as intimately as John Mastronardo, a convicted gambler and the younger brother of one of the country's biggest bookies. Mastronardo, who says he worked for Walters from 2000 to 2005, calls his former boss a genius. But he also witnessed what he saw as a dark side -- Walters could be cunning and openly malicious, he says.

Mastronardo, who has also dabbled as a bookie and worked in the Caribbean as an offshore sportsbook operator, says he and 20 or so underlings moved bets for Walters from Philadelphia before he moved to Las Vegas to work out of Walters' headquarters in exchange for a 25 percent cut of the winnings. "At times, he would give me $1 million to hold, $2 million to hold, with no signed contract," Mastronardo says. "I was betting it for him, so he staked me a bankroll.

Holding court in his airy fifth-floor beach condo in Boca Raton, Florida, Mastronardo, 59, looks fit and tanned, like he just walked off the golf course. But any day now, he will settle into a federal prison for a nine-month stay, the price for pleading guilty last year to illegal gambling and racketeering charges in connection with his post-Walters operation.

While many former associates fear speaking openly about Walters' business, Mastronardo says he has little to be afraid of. Talking about his past work helps ease some of the pain and embarrassment he's caused his family after more than 15 arrests, he says, adding that he's sought counseling to overcome his shame.

Mastronardo, an All-American wide receiver at Villanova and 10th-round pick of the Philadelphia Eagles in 1977, says he first met Walters in the 1980s while playing in a golf tournament for high-rolling gamblers hosted by Jack Binion, who owned a large casino in Vegas. Nearly two decades later, he says, the connection paid off when Walters asked him to move games.

One of Walters' major advantages, Mastronardo says, is his focus on smaller college games, which don't attract much action and thus often aren't researched as deeply by bookmakers. "Where they used to make a lot of money was on what they used to consider write-in games, that small college game where I didn't even know they had a line on it," Mastronardo says. "You might have a 7-point favorite with two no-name teams and the underdog would win by 15. Billy's art was to keep that game close to 7 and bet as much as you can without the world finding out about it."

One memorable night, Mastronardo says, he was at dinner with Walters and his wife when Walters began asking about a basketball game. "He says, 'What did that Old Dominion game open at?' I said '1.' He says, 'What did it close?' I said '1.' He says, 'I put $250,000 on Old Dominion tonight, and nobody knows about it.'

"That to me is genius," Mastronardo continues. "First of all, nobody knows where he bet it. Now you can bet in foreign markets. Some he bets in the casino. Some he bets offshore. Some he bets in different markets. So he uses the market however he wants. But the art was that he could bet a game for a lot of money and nobody would know about it."

But there were reminders that Walters could also be ruthless. Mastronardo recalls flying first class to Vegas with a duffel bag stuffed with more than $200,000 in cash for Walters. Federal agents stopped him before he could leave the bustling McCarran airport terminal and began pressing him to turn over the money, which they suspected was earned illegally. Mastronardo managed to get a message to Walters through Fats, a driver sent to the airport to pick him up. The reply from Walters was matter-of-fact: "Tell John good luck."

After several hours of questioning, agents accepted Mastronardo's defense that he was a professional gambler and allowed him to leave with the money. But the next morning, after Walters got his cash, he issued Mastronardo a warning: "He says, 'Johnny, you know the rules, right?' He says, 'That money was for me. If I don't get the money, it means I didn't receive the money. It means you are on the hook.' And he is right. That is the way it is."

Years later, when Mastronardo was operating an offshore sportsbook, he believes Walters planted a whale -- betting parlance for a high roller -- to hit his business. The suspect was a well-known Hollywood star who wanted to bet $100,000 a game, though Mastronardo became convinced that the actor didn't know anything about football. But after about three weeks, the man was winning so often that Mastronardo shut down his account, suspecting Walters had smartened him up.

"Billy knew it was me, and I used to have a relationship. But it is all fair in love and war," Mastronardo says, shaking his head. "Billy is very, very smart. And he is very cunning. He is kind of like a boxer you don't like personally but you respect his skill. Tiger Woods in his prime. You don't like the person, but you like the golfer."

For his part, Walters says he hasn't spoken with Mastronardo in 15 years. "Well, I don't recall him moving any money for me," he says. "I do know John Mastronardo. I don't recall having any relationship with him. He was a gambler, bet on sports, good golfer and a very personable guy."

While many former associates fear speaking openly about Walters' business, Mastronardo says he has little to be afraid of. Talking about his past work helps ease some of the pain and embarrassment he's caused his family after more than 15 arrests, he says, adding that he's sought counseling to overcome his shame.

Mastronardo, an All-American wide receiver at Villanova and 10th-round pick of the Philadelphia Eagles in 1977, says he first met Walters in the 1980s while playing in a golf tournament for high-rolling gamblers hosted by Jack Binion, who owned a large casino in Vegas. Nearly two decades later, he says, the connection paid off when Walters asked him to move games.

One of Walters' major advantages, Mastronardo says, is his focus on smaller college games, which don't attract much action and thus often aren't researched as deeply by bookmakers. "Where they used to make a lot of money was on what they used to consider write-in games, that small college game where I didn't even know they had a line on it," Mastronardo says. "You might have a 7-point favorite with two no-name teams and the underdog would win by 15. Billy's art was to keep that game close to 7 and bet as much as you can without the world finding out about it."

One memorable night, Mastronardo says, he was at dinner with Walters and his wife when Walters began asking about a basketball game. "He says, 'What did that Old Dominion game open at?' I said '1.' He says, 'What did it close?' I said '1.' He says, 'I put $250,000 on Old Dominion tonight, and nobody knows about it.'

"That to me is genius," Mastronardo continues. "First of all, nobody knows where he bet it. Now you can bet in foreign markets. Some he bets in the casino. Some he bets offshore. Some he bets in different markets. So he uses the market however he wants. But the art was that he could bet a game for a lot of money and nobody would know about it."

But there were reminders that Walters could also be ruthless. Mastronardo recalls flying first class to Vegas with a duffel bag stuffed with more than $200,000 in cash for Walters. Federal agents stopped him before he could leave the bustling McCarran airport terminal and began pressing him to turn over the money, which they suspected was earned illegally. Mastronardo managed to get a message to Walters through Fats, a driver sent to the airport to pick him up. The reply from Walters was matter-of-fact: "Tell John good luck."

After several hours of questioning, agents accepted Mastronardo's defense that he was a professional gambler and allowed him to leave with the money. But the next morning, after Walters got his cash, he issued Mastronardo a warning: "He says, 'Johnny, you know the rules, right?' He says, 'That money was for me. If I don't get the money, it means I didn't receive the money. It means you are on the hook.' And he is right. That is the way it is."

Years later, when Mastronardo was operating an offshore sportsbook, he believes Walters planted a whale -- betting parlance for a high roller -- to hit his business. The suspect was a well-known Hollywood star who wanted to bet $100,000 a game, though Mastronardo became convinced that the actor didn't know anything about football. But after about three weeks, the man was winning so often that Mastronardo shut down his account, suspecting Walters had smartened him up.

"Billy knew it was me, and I used to have a relationship. But it is all fair in love and war," Mastronardo says, shaking his head. "Billy is very, very smart. And he is very cunning. He is kind of like a boxer you don't like personally but you respect his skill. Tiger Woods in his prime. You don't like the person, but you like the golfer."

For his part, Walters says he hasn't spoken with Mastronardo in 15 years. "Well, I don't recall him moving any money for me," he says. "I do know John Mastronardo. I don't recall having any relationship with him. He was a gambler, bet on sports, good golfer and a very personable guy."

LAST MAY NEWS of Walters' latest legal headache went public: The Wall Street Journal and New York Times reported that he, Mickelson and investor Icahn were being investigated for insider trading. Authorities suspected that Icahn had tipped off Walters about potential investments that would have affected the price of two stocks and that Walters had informed his friend Mickelson.

Mickelson has since been cleared on one of two inquiries, but the investigation remains open -- though no charges have been filed and authorities refuse to discuss the case. If Walters is never prosecuted, the investigation would join a long list of occasions on which authorities have tried and failed to bring him down. Many politicians, investigators and prosecutors asked that their name not be used in this story, lest Walters tie them up in a lawsuit they can't afford to fight.

Walters' closest call happened 30 years ago, when the FBI conducted raids against the Computer Group in 16 states. Walters was a key member of the group's operations, Assistant U.S. Attorney Eric Johnson says: "[He] was responsible for getting the bets out. And he had a whole series of bookmakers who were willing to take a bet and send bets out to other people, because they wanted to get that information first, so as soon as they took the bet from the Computer Group they could change their line before they got hit."

Walters maintained his innocence, and he was acquitted in a trial filled with plot twists. Just ahead of trial, he won a stroke of luck better than pocket aces. Jane Shoemaker, an inexperienced prosecutor new to the Vegas office, was handed the case. Then the government's star witness -- who was to be responsible for guiding jurors through allegedly incriminating evidence from seized records and audiotapes -- suffered a heart attack the night before he was to testify.

"He's like Tiger Woods in his prime. You don't like the person, but you like the golfer."

<cite>- John Mastronardo</cite>

Then Walters got even luckier. U.S. District Judge Lloyd D. George, a staunch conservative with a reputation for favoring prosecutors, invited him to meet with the lead FBI investigator on the case. George said the meeting would take place only if Walters did not inform his attorney, Oscar Goodman, who had become famous for representing mobsters and would later be elected mayor of Las Vegas. Walters didn't inform Goodman in advance, but he told him after the fact, according to John L. Smith, who wrote a biography on Goodman. Outraged, the attorney filed a motion to dismiss the case. To allow it to proceed, George recused himself, and he was replaced by a liberal-leaning judge from Pennsylvania. The jury voted not guilty on 64 counts and failed to reach a consensus on 54 others -- which the government dismissed rather than prosecute again. In Computer Group founder Mindlin's opinion, "the judge had to recuse himself, and that is what saved us."

Some people suspect that Walters has helped himself stay out of trouble by giving investigators information. Walters denies the allegation, saying all he did was answer questions about the differences between gambling and bookmaking during the Computer Group case. "I've never been an informant," he says. "There is a big difference between answering a question for law enforcement to try to get an issue to go away and being a goddamn informant. I am a lot of things, but I am not stupid. If I was gonna be an informant, I would assure you I would have negotiated a deal that I never would have been indicted for betting on sports."

After Goodman found out that Walters had cooperated with law enforcement during the Computer Group prosecution, the two parted ways. Walters says he removed his attorney; Goodman told Smith he quit the case. The two later made up, and when the flamboyant defense attorney ran for re-election as mayor in 2003, Walters hosted a fundraiser at his golf course on the Vegas Strip, raising $400,000. Goodman initially agreed to be interviewed for this story but changed his mind at the last minute. "It is so long ago," he says, "it's like digging up a ghost."

And like a ghost, Walters seemingly can't be touched. Even many of those who have tried to bring him down admit a grudging respect. After David L. Thompson -- then a Nevada deputy attorney general -- unsuccessfully prosecuted Walters on money-laundering charges in the early 2000s, he was forced to resign. Now, as federal officials decide whether to move forward with the insider-trading case, Thompson offers his own nickname for William T. Walters.

"The Fortunate Mr. Walters," he says. "Because everything always seems to work out his way."

Mike Fish is an investigative reporter for ESPN.com. Follow him on Twitter: @MikeFishESPN or email him here.

Follow ESPN Reader on Twitter: @ESPN_Reader.

Join the conversation about "A Life On The Line.

Mickelson has since been cleared on one of two inquiries, but the investigation remains open -- though no charges have been filed and authorities refuse to discuss the case. If Walters is never prosecuted, the investigation would join a long list of occasions on which authorities have tried and failed to bring him down. Many politicians, investigators and prosecutors asked that their name not be used in this story, lest Walters tie them up in a lawsuit they can't afford to fight.

Walters' closest call happened 30 years ago, when the FBI conducted raids against the Computer Group in 16 states. Walters was a key member of the group's operations, Assistant U.S. Attorney Eric Johnson says: "[He] was responsible for getting the bets out. And he had a whole series of bookmakers who were willing to take a bet and send bets out to other people, because they wanted to get that information first, so as soon as they took the bet from the Computer Group they could change their line before they got hit."

Walters maintained his innocence, and he was acquitted in a trial filled with plot twists. Just ahead of trial, he won a stroke of luck better than pocket aces. Jane Shoemaker, an inexperienced prosecutor new to the Vegas office, was handed the case. Then the government's star witness -- who was to be responsible for guiding jurors through allegedly incriminating evidence from seized records and audiotapes -- suffered a heart attack the night before he was to testify.

"He's like Tiger Woods in his prime. You don't like the person, but you like the golfer."

<cite>- John Mastronardo</cite>

Then Walters got even luckier. U.S. District Judge Lloyd D. George, a staunch conservative with a reputation for favoring prosecutors, invited him to meet with the lead FBI investigator on the case. George said the meeting would take place only if Walters did not inform his attorney, Oscar Goodman, who had become famous for representing mobsters and would later be elected mayor of Las Vegas. Walters didn't inform Goodman in advance, but he told him after the fact, according to John L. Smith, who wrote a biography on Goodman. Outraged, the attorney filed a motion to dismiss the case. To allow it to proceed, George recused himself, and he was replaced by a liberal-leaning judge from Pennsylvania. The jury voted not guilty on 64 counts and failed to reach a consensus on 54 others -- which the government dismissed rather than prosecute again. In Computer Group founder Mindlin's opinion, "the judge had to recuse himself, and that is what saved us."

Some people suspect that Walters has helped himself stay out of trouble by giving investigators information. Walters denies the allegation, saying all he did was answer questions about the differences between gambling and bookmaking during the Computer Group case. "I've never been an informant," he says. "There is a big difference between answering a question for law enforcement to try to get an issue to go away and being a goddamn informant. I am a lot of things, but I am not stupid. If I was gonna be an informant, I would assure you I would have negotiated a deal that I never would have been indicted for betting on sports."

After Goodman found out that Walters had cooperated with law enforcement during the Computer Group prosecution, the two parted ways. Walters says he removed his attorney; Goodman told Smith he quit the case. The two later made up, and when the flamboyant defense attorney ran for re-election as mayor in 2003, Walters hosted a fundraiser at his golf course on the Vegas Strip, raising $400,000. Goodman initially agreed to be interviewed for this story but changed his mind at the last minute. "It is so long ago," he says, "it's like digging up a ghost."

And like a ghost, Walters seemingly can't be touched. Even many of those who have tried to bring him down admit a grudging respect. After David L. Thompson -- then a Nevada deputy attorney general -- unsuccessfully prosecuted Walters on money-laundering charges in the early 2000s, he was forced to resign. Now, as federal officials decide whether to move forward with the insider-trading case, Thompson offers his own nickname for William T. Walters.

"The Fortunate Mr. Walters," he says. "Because everything always seems to work out his way."

Mike Fish is an investigative reporter for ESPN.com. Follow him on Twitter: @MikeFishESPN or email him here.

Follow ESPN Reader on Twitter: @ESPN_Reader.

Join the conversation about "A Life On The Line.

Billy Walters = the Teflon Don

Today, sources say, the headquarters of Walters' international operation is located outside the United States. The last known location was in Panama, according to sources, after earlier offices were based in London, the Bahamas and Tijuana, Mexico. "Very little happens here," one source familiar with Walters' operation says of the group's Vegas-based gambling.

If they legalized sports betting in most states in the US, he would be back with full force.

If they legalized sports betting in most states in the US, he would be back with full force.

Doubt it. The article even referenced that Billy Walters spends less than 7% of his time on sports wagering. He has taken an incredibly successful gambling enterprise and done the smart thing- use that money to invest in legitimate business ventures and diversify. Walters won't be placing bets through runners when he can be placing calls into board rooms of companies he has majority stake in. That's the difference between rich and wealthy.

He has his hands in everything.........the percentage of money he use to win in sports is way less than it use to be because gone are the days where he & his team had more of an advantage.

Doubt it. The article even referenced that Billy Walters spends less than 7% of his time on sports wagering. He has taken an incredibly successful gambling enterprise and done the smart thing- use that money to invest in legitimate business ventures and diversify. Walters won't be placing bets through runners when he can be placing calls into board rooms of companies he has majority stake in. That's the difference between rich and wealthy.

+1

<

<