[h=4]When To Watch[/h]

All five parts available on WatchESPN June 14

Available for DVD preorder

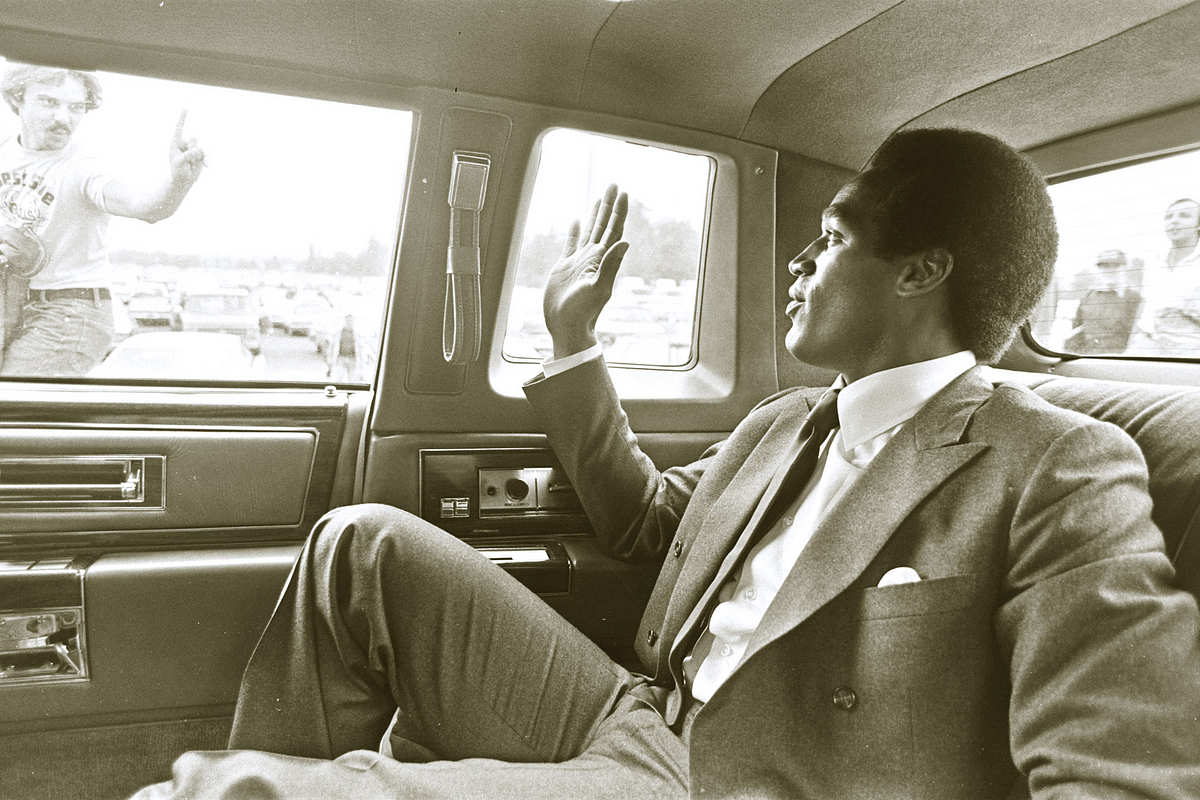

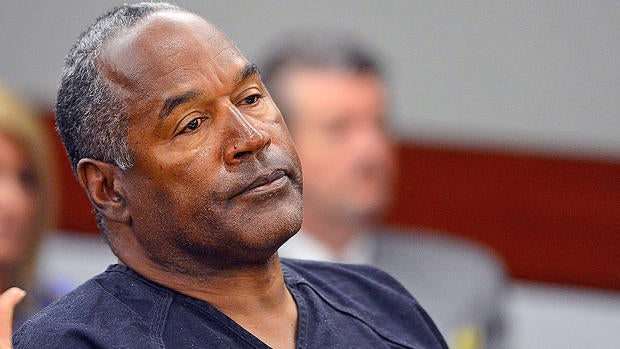

[h=2]O.J.: Made In America[/h]

- Part 1

- Sat. June 11, 9 p.m. ET on ABC - Premiere

- Tue. June 14, 7 p.m. ET on ESPN - Re-air

- Part 2

- Tue. June 14, 9 p.m. ET on ESPN - Premiere

- Wed. June 15, 7 p.m. ET on ESPN - Re-air

- Part 3

- Wed. June 15, 9 p.m. ET on ESPN - Premiere

- Fri. June 17, 7 p.m. ET on ESPN - Re-air

- Part 4

- Fri. June 17, 9 p.m. ET on ESPN - Premiere

- Sat. June 18, 7 p.m. ET on ESPN - Re-air

- Part 5

- Sat. June 18, 9 p.m. ET on ESPN - Premiere

All five parts available on WatchESPN June 14

Available for DVD preorder

[h=2]O.J.: Made In America[/h]